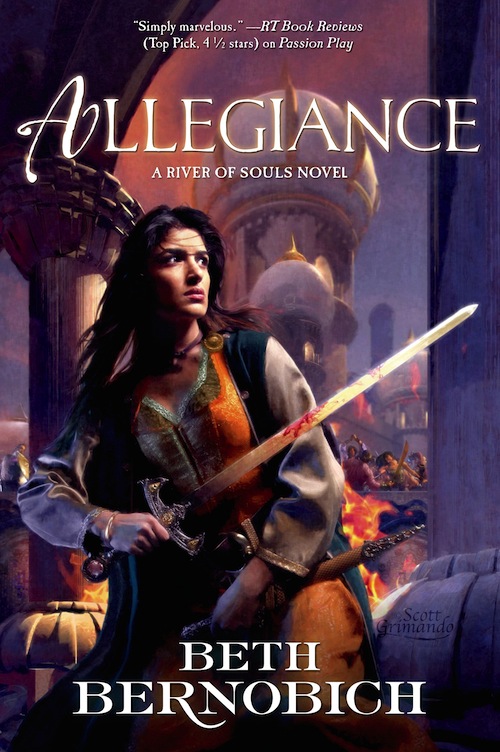

Check out Allegiance, the conclusion to Beth Bernobich’s River of Souls trilogy, available October 29th from Tor Books!

King Leos of Károví, the tyrannical despot whose magic made him near immortal, is finally dead. Ilse Zhalina watched as the magical jewels that gave him such power reunited into a single essence, a manifestly God-like creature who then disappeared into the cosmic void. Ilse is now free to fulfill her promise to Valara Baussay, the rogue Queen of Morennioù, who wants to return to her kingdom and claim her throne.

Pulled by duty and honor, Ilse makes this long journey back to where her story began, to complete the journey she attempted lives and centuries before and bring peace between the kingdoms. Along the way she learns some hard truths and finally comes to a crossroads of power and magic. She must decide if duty is stronger than a love that she has sought through countless lifetimes. Will Isle give up her heart’s desire so that her nation can finally know lasting peace?

CHAPTER ONE

Endings, the poet Tanja Duhr once wrote, were deceptive things. No story truly came to a final stop, no poem described the last of the last—they could not, not until the world and the gods and time had ceased to exist. An ending was a literary device. In truth, the end of one story, or one life, carried the seeds for the next.

The idea of seeds and new beginnings offered Ilse Zhalina little consolation.

It was late summer, the season tipping over into autumn, and dawn wrapped the skies in murky gray. Six weeks had passed since she had abandoned Raul Kosenmark on Hallau Island. Her last glimpse had been of him fighting off an impossible number of enemy soldiers. Ten days ago, Leos of Károví, once called the immortal king, had died, and she had witnessed Lir’s jewels reunited into a single alien creature, who then disappeared into the magical void. Endings upon endings, to be sure, and some of them she had not yet begun to comprehend. And yet she lived on, she and Valara Baussay.

Ilse crouched over the ashes of their campfire and rubbed her hands together, trying to warm them. The air was chill, stinking of sweat and smoke. In the first few days of their flight, Ilse had been convinced they would never survive. Inadequate clothing, inadequate supplies. She had since acquired a knitted cap and a woolen coat, once the property of a man much taller and heavier than she. He was dead now. A sword slash, ringed with bloodstains, marked where she had killed him. Underneath, she still wore her own cotton shirt from Hallau Island. If she allowed herself, if she let imagination take flight, she might catch the faded scent of days long past, of that brief interlude with Raul Kosenmark.

Raul. My love.

She pressed both hands against her eyes. She was hungry, hungry and cold and consumed by an emptiness that was greater than any physical need. She wished… oh, but to wish for Raul was impossible. She would only start weeping, and she could not grant herself the luxury of grief, not yet. Not until she and Valara Baussay had escaped this hostile land.

Her breath shivering inside her, she wished instead for a scalding hot fire. A perfumed bath, too. At the thought of scented baths in this wilderness, she almost laughed, but it was a breathless, painful laugh, and she had to pause and recover herself before she could continue her list of wants and desires. Clean clothes, strong coffee, a book to read in warmth and quiet. A feast of roasted lamb, fresh melon, and steamed rice mixed with green peppercorn.

Her imagination failed her at the subsequent courses. There could be no fire until daybreak, not unless she wished to signal her presence to any chance patrols from the western garrisons. The skies had lightened with the approaching dawn, but day came as slowly as the night, here in the far north of Károví. It would be another hour before she could risk a fire. She shuddered from the cold and the thought of enemies in pursuit.

Her companion in this madness, Valara Baussay, slept wrapped tightly in a blanket, and as close to the fire as possible. In the dim light, only the darkest and largest of her tattoos, at the outside corner of her left eye, was visible—an elaborate pattern of interlocking squares, drawn in reddishbrown ink, that formed a diamond. A second, simpler pattern under her lower lip was indistinguishable in the shadows. Symbols of nobility or rank, Ilse guessed, though Valara had said nothing of their meaning in the few months of their acquaintanceship. It was difficult to remember, when Valara slept, that she was a queen of Morennioù. Awake, it was impossible to forget.

We have never been true friends, not in any of our lives. But from time to time, we have been good allies.

Not in every life. They had been enemies as well, or if not true enemies, then in conflict with each other. Four hundred years ago, in one of those past lives, Valara had been a prince of Károví. As Andrej Dzavek, he and his brother had stolen Lir’s jewels from the emperor, then fled to their homeland, in those days a princedom of the empire. In that same life, Ilse had been a princess betrothed to Leos Dzavek in a political marriage.

Andrej Dzavek had regretted his treason. He had led the imperial armies against Károví and his brother, only to die on the battlefield. Ilse Zhalina had attempted to negotiate a peace between the kingdoms. Leos Dzavek had executed her, and with the jewels’ magic, lived on for centuries. At some point, Ilse and Valara Baussay would both have to confront all the complications of their past lives.

Her hands were as warm as she could make them. Ilse tugged her knitted cap low over her forehead and drew her hands inside the sleeves of her ill-fitting coat. Moving as quietly as she could manage, she crept up the slope and peered between the two slabs of rock that overshadowed their campsite. From here, she had a clear view of the surrounding plains. They had made camp, such as it was, in a narrow fold of land, its banks strewn with rocks. Pine and spruce once grew here, but now only a few dead trees remained. At the bottom of the fold ran a stream, fed by summer rains and meltwater from the western mountains. A cold uncomfortable site, but for now, she was grateful to have wood for fire, water to drink, and a shelter to hide in.

All was quiet. Rain had fallen in the night, and a cool damp breeze blew from the west, carrying with it the tang of mountain pines, like magic’s sharp green fragrance, and the earthier scents of mud and grass and wildflowers. Even as she watched, a thin ribbon of light unfurled along the eastern horizon, changing the black expanse into a pale ocean of grass, bowing in wave after wave, like those from the far-off seas. That looming mass of shadow to the west would be the Železny Mountains, which divided the Károvín plains from the kingdom’s westernmost province of Duszranjo. Within a day’s march was where she and Valara were to meet with Duke Miro Karasek.

A flicker of shadow caught her eye—a blurred speck of movement in the grass. Ilse unhooked the buttons of her coat and checked her few weapons—the sword at her belt, the knife in her boot, and the one in her wrist sheath. All were within easy reach. She stared at the point where she had sighted the shadow. Not a patrol, she told herself. It was too small and swift a movement. A solitary rider?

Then the light ticked upward, and she saw what it was—a fox, gliding through the tall grass. A breath of laughter escaped her. She eased back toward the banked fire. Valara stirred and muttered in her own language. Was she dreaming of past lives?

I’ve dreamed. I’ve never stopped dreaming since Leos died.

She rubbed her forehead with the back of her wrist.

…Leos Dzavek’s hand tightened around the ruby jewel, its light spilling through his fingers like blood… Magic burst against magic, and the world exploded. When she could see again, she saw Leos crushed beneath the marble pedestal, his eyes blank and white, like a winter snowfall. He was dying, dying, dying but he would not release his hold upon her, and she felt her soul slipping into the void between worlds…

No! Dzavek was dead, his soul was in flight to its next life, and the jewels had returned as one to the magical plane. She had fulfilled her obligations to the gods. She pulled off the cap and raked her fingers through her knotted hair. The lurid images of her nightmare faded into the pale red light of sunrise.

She drew a sharp breath in surprise.

Valara Baussay was awake and studying Ilse with those brilliant brown eyes. Though Valara’s expression seldom betrayed anything, and even those few clues were often deliberate indirection, Ilse had the impression of being constantly assessed by her companion. In that she was much like Raul.

“You didn’t wake me for my watch,” Valara said.

“No. You were tired and—”

“—and you were afraid of your nightmares. Was it the same one as before?”

Her voice was uncharacteristically gentle.

“The same one, yes.”

“Ah. I have them, too.”

Ilse glanced up, suddenly wary. “You never said so before.”

Valara shrugged. “I don’t like to think about it.”

Ah, well. Ilse could understand that.

“I’ll restart the fire,” she said. “We can eat breakfast and make an early start.”

“Breakfast.” Valara’s mouth softened into a pensive smile. “I’ve dreamed of breakfast, too, from time to time.”

She stood up and stretched. She wore the dead courier’s gloves and his shirt over her own. Valara had rolled up the sleeves and tied a makeshift sash, but her thin frame was almost lost in the folds. Even dressed in such a mismatched costume, she had the air of one about to issue a royal decree— yet another similarity to Raul.

“What is wrong?” Valara asked.

“Nothing,” Ilse said quickly. “Nothing we can change.”

Valara regarded her with narrowed eyes. “As you say,” she murmured.

She headed downstream to the trench Ilse had dug for their latrine. Ilse collected tinder and a few larger branches, and coaxed their fire into life. She set a pan of water to boil and refilled their waterskins. A brief inspection of their supplies was discouraging: a handful of tea leaves, enough smoked beef for a good breakfast but nothing for midday, and a few dried apples. They had eaten the last of the courier’s flatbread the night before. Karasek had provided them with as much gear and provisions as he could spare, but it had all been so haphazard, those final hours at the Mantharah. Hiding all traces of their camp, including their magic. Working out their escape, and how Karasek might lead the search in the opposite direction. What came next, after they were certain they were safe.

Ilse blew out a breath. After. Yes.

If I were wishing, I would wish for Raul. I would wish we were together in Tiralien, without any fear of war between our kingdom and Károví. Without balancing every act against what Markus Khandarr might do against us. We could be Stefan and Anike, two ordinary people, living ordinary lives.

Impossible wishes. Ilse had promised Valara she would sail with her to her island kingdom, a hostage for peace, in return for Valara’s help in recovering the last of Lir’s jewels. She could argue the vows no longer applied. Dzavek was dead. The jewels had departed from the ordinary world. All the variables she and Raul had depended upon had vanished or changed in unpredictable ways.

Including Raul himself.

We are creatures of nothing, she thought. Caught between lives and obligations. We have no certain ending, nor any sign of what comes next.

Or perhaps she had not understood the true import of her previous lives.

It was an uncomfortable idea.

Within the hour, they broke their fast with hot tea and smoked beef, saving the apples for midday. Their stomachs were full, at least temporarily. With the sun glancing over the fields, and the frost melting under the summer sun, Ilse and Valara cleared away all signs of their camp, refilled their waterskins, and set off on foot over the Károvín plains.

Progress was slow. Foraging proved less productive than they liked.

Even so, by late afternoon, they were within sight of their destination. A midday hailstorm had ended, leaving intermittent rain showers in its wake. Clouds still veiled the skies and the air shimmered wet and gray.

They took cover in a thicket of scrub and sapling pines, while Ilse scanned the open ground ahead. A grassy slope dipped toward a shallow ravine and creek swollen by rain. A stand of trees on the farther ridge marked a more substantial streambed beyond. According to all her calculations, every landmark, and instructions from the man himself, those trees and that streambed marked where Duke Karasek had appointed to meet them.

An empty landscape met her eye. She saw no sign of movement, other than needles trembling under raindrops, but she had been deceived once before. She wore the memory of that encounter.

…a startled man dressed in military garb. His grin as he saw two women alone, on foot. Ilse drawing her sword, speaking words of magic to blind him. Moments later, the sun slanting through leaves spattered with blood…

The nearest garrison lay almost fifty miles away, she told herself. Patrols were not likely. Nor should they encounter any trappers or chance travelers in this wild region. She leaned toward Valara and whispered, “I’ll scout ahead. Wait for my signal.”

She rose slowly to her feet, checked her sword and knives, then crept forward into the ravine, down, step by cautious step, across the bare ground, to the meltwater stream at the bottom and up the farther side.

At the top of the bank, she peered over the edge. More thornbushes covered the ground here. The stand of pines lay directly ahead. From a distance came the rill of running water. A bird, a tiny brown wren, flitted from one branch to another, but otherwise, all was still.

She whistled, a brief warbling cry, to signal all clear. Valara scrambled down the bank and across the open expanse to join her. No sooner had she done so than Ilse heard the distinct whicker of a horse.

Valara froze. “More patrols?” she whispered.

“Or our friend.” Then Ilse broached the subject she had not dared to, five days before, after their encounter with the courier. “We might need to use magic—”

“I cannot. I— Never mind why. I cannot.”

You were ready that other time, in Osterling Keep. You killed a dozen men with words alone. And on Hallau Island, too.

But not once since their confrontation with Leos Dzavek.

Yet another subject for later.

“Wait here,” she whispered. “I’ll scout ahead. If that horse belongs to Karasek, I’ll give our other safe signal. Otherwise, make your escape, and I’ll do whatever I need to.”

Valara nodded. She understood. They could not risk discovery. If Ilse were attacked, she would kill their enemies with sword and magic.

Ilse crawled forward, wriggling through the mud until the thornbushes gave way to the pine trees. Cautiously she rose to a crouch and continued farther into the trees. Saplings grew thickly among the older pines and the air was ripe with their tang. As her eyes adjusted to the shadows, she could make out a clearing ahead, and three horses on the far side. Two of them were plain, hairy beasts, as short as ponies. The third was a long-legged creature, a mount fit for a royal courier—or a duke.

The hiss of a branch was her only warning. She sprang to her feet and reached for her sword. Before she could slide the blade free, an arm crashed into her face. Ilse staggered back, tucked into a ball to roll free, but a hand grabbed her shoulder and swung her around. She slammed against the stranger’s chest, breathless and stunned.

But now the hours of drill with Benedikt Ault took control. Ilse kicked back, driving her heel against her attacker’s shin. The moment his grip loosened, she spun around and drew her sword.

“Ei rûf ane gôtter…

“…ane Lir unde Toc…”

Two summonses to the magic current. Two invocations to the gods, delivered in old Erythandran. The air split, as though divided by a knife, an infinitesimal void running between Ilse and her attacker. Bright magic rushed through. It filled the clearing with a sharp green scent, overpowering the pine tang. Like a wind diverted from a larger storm, it blew hard against Ilse’s face. Ilse gripped her sword, trying to peer through the brilliant haze of magic. Her own signature was strong and unmistakable, starlight glancing through clouds. His came fainter, sunlight reflected from snow-crested mountains.

I know that signature.

She whispered the words to recall the magical current. The brightness faded.

Miro Karasek crouched a few yards away, his sword angled up and outward, ready to strike. The branches above swung to and fro, casting raindrops over them both. It was hard to make out much in the gray-green shadows, but Ilse could see the dark circles under his eyes, the lines drawn sharp beside his mouth. The past two weeks had cost him much.

Miro bent to massage his shin. “I warned you against using magic.”

Ilse ran her tongue over her swollen lip. “And I do not like games. Why did you attack?”

“My apologies for the roughness,” he said. “I didn’t recognize you.”

And thought her a brigand—or worse. Her hands shaking, Ilse sheathed her sword. “You have news?”

He nodded. “Where is her highness, the queen?”

He did not say whether the news was good or bad, and Ilse did not press him. She gave a short shrill whistle to signal all-safe. Within moments Valara appeared, pushing the low-hanging branches to one side, as if they were curtains in a palace. She spared a glance toward Ilse, but her attention was for Miro Karasek.

His gaze caught hers, then flicked away. “They are hunting north and east,” he said. He gestured toward the clearing. “I can tell you more after you eat. You will be starving, and I want you able to pay attention.”

Before long they were seated close to a campfire and shedding their filthiest, dampest outer garments. It was not exactly Ilse’s dream of wishes, but nearly so. She greedily drank the soup Miro Karasek offered, followed by a mug of tea. The tea was strong and black, sweetened with honey. Before she had finished it, she found a second panniken of soup waiting, along with a flat disk of camp bread.

Valara waved away her second helping of soup. “Tell us what happened at Rastov. No, before that. Start from the day you left us.”

Her voice was short and sharp. Ilse stiffened. Would Karasek recognize the panic?

Karasek stirred the coals, betraying nothing of his thoughts. “There is not much to tell. You remember how we worked to mislead any trackers from Duke Markov? I decided that was not sufficient. Markov has a number of mages in his employ, not to mention his ally, Duke Černosek. If they once decided to search beyond Mantharah, they would overtake you within days. So I prepared other clues farther to the east.”

As he fed the fire with more sticks, he told them of creating the apparent signs of a large camp between Károví’s capital city of Rastov and Mantharah, then a distinct trail leading northeast toward a remote inlet. It had taken him the entire day and half of the next.

“I returned to Rastov by the following morning—”

“What did they say about the king?” Valara said.

He regarded her with a long, impenetrable look. “They say he died. And that someone killed him.”

Valara subsided. It was a matter of technicalities, who or what had killed Leos Dzavek. Ilse had distracted him. Valara had infuriated him. In the end, Lir’s jewels had unleashed the magic to kill the immortal king, but they could not have done so without each small step and sidestep in between. We are all complicit, including Leos himself.

“What about those horses?” she said. “You didn’t take those from a garrison.”

“The horses are for you. I acquired them discreetly, along with these maps…”

He went to his mount and extracted several scrolls from a pouch. These were maps of the regions, wrapped in oilskin against the uncertain summer rains. Now Ilse could see clearly the reasons behind his instructions from ten days before—the way they had circled around Rastov toward the mountains, how their path would parallel his as they proceeded south into the central plains, and the point where they would turn east into Karasek’s duchy of Taboresk, where he would rejoin them.

“I have new provisions and more gear,” he continued.

Obtained from garrison stores, and at the risk of discovery.

Ilse hesitated to ask. Valara had no qualms. “Does anyone suspect?” she asked.

This time there was no pause before he answered.

“Duke Markov might,” he said. “I arrived, almost coincidentally, at the crisis. I took it upon myself to track the assassins. In his eyes, that will appear unusual enough for suspicion. But he cannot afford to offend me, nor I him. What of you?”

“We survived,” Valara said. “Anything else is superfluous.”

Karasek’s eyes narrowed and he studied her a long moment. “As you say,” he said slowly.

He divvied the chores and watches with no more consideration than if they were his most junior recruits. Ilse dug a new latrine away from the stream and their camp. Valara took the early watch, which included tending to the horses and washing all the dishes.

I am a queen of Morennioù, she thought with a rueful smile. I should not have to wash dishes.

She remembered what her father said once, years ago, when Valara and her sister had rebelled against tending to their own horses. She was a princess, Franseza had declared. She would not care for such dirty creatures. Certainly she would not muck out their stalls.

“Then you can never be queen,” Mikaël of Morennioù told his daughter. “This horse is your servant. You owe her this service in return for her service to you. If you refuse this small task, then you refuse the throne and the crown. Else how can I trust you with the greater duty of ruling the kingdom when I die?”

Shocked, Franseza never again protested such chores. Nor had Valara, even though she was the younger daughter, and therefore not called to the throne. Of course, that was before Franseza and their mother died at sea.

I want to earn that throne, Valara thought. I want to be queen, the way my father was king.

So she bent herself to scrubbing out pots.

She soon needed more water to rinse the dishes. Valara took up the largest waterskin and set off to find the stream. Miro had pointed out the direction before he went to sleep, but he had not mentioned how thickly the trees grew. She had to pick her way between and around the saplings and underbrush, pausing now and then to free her sleeve from a prickly vine. By the time she reached the lip of the ravine, the camp was no longer visible. There was not even a glimmer of firelight.

I will not shout for help.

As if in answer, one of the horses snorted. Valara laughed softly. She fixed the direction of that helpful snort in her memory and turned back to her task. The ravine’s bank was steep. She had to scramble down from outcropping to outcropping, sometimes on her hands and knees, and barely missed falling into the stream itself. Cursing to herself, she filled the waterskin and dried her hands on her shirt.

The last of the sunlight had bled from the sky during her climb down the bank. The skies had turned violet, with wisps of dark clouds obscuring the stars. A breeze from the east carried with it the scents of summer from the open plains. Farther and fainter came the cold scent of the coming winter.

Home seemed so very distant.

She blew out a breath. Let us eradicate one obstacle after another. She slung the waterskin’s strap over her shoulder and clambered up the bank. She had almost attained the summit when a shadow loomed over her. Valara started back. Miro Karasek caught her by the arm before she tumbled down the bank.

“You were gone longer than I expected,” he said.

“You were watching?”

“No. But the horses woke me.”

He helped her up the last few yards of the bank. To her relief, he remained silent as they threaded through the bushes and back to the camp. Even so, she remained preternaturally aware of his presence at her side, and later as he settled easily onto his bed of blankets, his gaze resting on her. Valara knelt by the fire and took up the next pot, adding hot water and soap before scrubbing it clean. “It’s not time for your watch,” she said. “You should sleep.”

“I will later. I had a question or two.”

When he did not continue, she swiped the rag inside the pot. She rinsed it clean of suds and set the pot upside down on the stones next to the fire where it could dry. The next was a metal pan, suited for baking flatbread. She dipped the pan into hot water and tilted it so the suds swirled around.

Allegiance © Beth Bernobich, 2013